The Creampuff of Sentimentality: Trends in Literary Censorship

The cat is now pretty well out of the bag.

Earlier this year, a famous liberal writer naively stumbled onto the fact that literary agents and publishers are actively engaged in discrimination, seeking only authors who fit into certain neat categories of identity. When she tweeted about this situation, it marked a shift in the culture. Something known only by those involved in the literary world had suddenly spilled over into public consciousness. Here’s how the writer, Joyce Carol Oates, put it in the tweet she no doubt now regrets sending:

"A friend who is a literary agent told me that he cannot even get editors to read first novels by young white male writers, no matter how good; they are just not interested. This is heartbreaking for writers who may, in fact, be brilliant, & critical of their own 'privilege.'”[1]

Unsurprisingly, Oates was excoriated by all the usual suspects for blowing the whistle on the importance of identity in the publishing world. That was in July. Two months later, the editor of a small literary magazine called Hobart Pulp decided to publish an interview with a Latino writer named Alex Perez. Perez is a graduate of the legendary Iowa Writer’s Workshop. He had a lot to say about current “woke” assumptions regarding writing and censorship, about literary gatekeepers and so on.

While few of his inconvenient but accurate observations would have been relevant 20 years ago, absolutely none of the substance of his critique would have been considered controversial then either. But in 2022, these observations were enough to cause angry denunciations from staff, a self-righteous “open letter,” and the resignation of half of the Hobart Pulp staff. Not only that, writers who wished to maintain their woke credentials began tweeting about how horrified they were to have ever published in the magazine. “Please remove a story of mine in your archives,” bleated one. “I hope you’re proud of yourself for destroying the goodwill and community that so many others have worked to build.”[2]

What did Perez say to cause so much hand wringing?

Explaining that today’s agents, editors and publishers all share the same ideological and typically the same socioeconomic background as well – he dubs them “Brooklyn ladies” – Perez tells us that

“Everyone knows these ladies took over, of course. Everyone querying agents knows this. Everyone dealing with a publicist knows this. If you follow one on Twitter, you follow them all. Every white girl from some liberal arts school wants the same kind of books…I’m interested in BIPOC voices and marginalized communities and white men are evil and all brown people are lovely and beautiful and America is awful and I voted for Hillary and shoved my head into a tote bag and cried cried cried when she lost…

“These women, perhaps the least diverse collection of people on the planet, decide who is worthy or unworthy of literary representation. Their worldview trickles down to the small journals, too, which are mostly run by woke young women or bored middle-aged housewives. This explains why everything reads and sounds the same, from major publishing houses to vanity zines with a readership of fifteen. The progressive/woke orthodoxy is the ideology that controls the entire publishing apparatus.”[3]

For these and similar observations, Perez and Hobart Pulp editor Elizabeth Ellen were vilified beyond all measure. Ironically, one the fussiest left-wing magazines in the English-speaking world had already confirmed Perez’s portrait of the “Brooklyn ladies” in 2016, when they published a piece demonstrating that U.S. publishing was roughly 80% female and white.[4] Clearly the goal there was to whine about the racial dimension, while ignoring the far more remarkable fact that such a large majority of all literary gatekeepers are female. What’s more, whites overall make up roughly 60% of the U.S. population – with a higher rate for the over 30s, precisely the demographic Perez mentioned. In other words, that publishing remains 80% white is far less remarkable than that it is now 80% female. Unsurprisingly, the Guardian focused on the less relevant fact, since it fit in better with the race fixation that is so important a part of current woke orthodoxy.

The uproar caused by both of these cases makes the issue suddenly very clear and visible: the literary world – from book publishing to small magazines and talent agencies – is controlled by an ideologically fixated cluster of true believers, as dedicated to censorship and morality policing as the most extreme religious activists from the turn of the last century. However different the reigning morality, it commands enough assent to set us up for a repeat of the Comstock era, in which religious busybodies managed to seize, destroy and prohibit the publication of classic works of art and literature.

Much has already been written on political censorship in the woke age. But literary censorship is a different animal. Where political censorship relies more on fraudulent “fact-checking,” charges of “hate-speech,” and the more subtle insinuation that something goes “against our values,” literary censorship is almost entirely a matter of suffocating talent before it can find any publication whatsoever. Where political writers of all viewpoints can find outlets willing to publish them, owing to the very nature of partisanship, literary writers suffer from the fact that literary magazines and publishing houses, long understood to be essentially neutral, have become monolithically ideological. The pundit knows and has always known that he must approach outlets which share his own point of view. But the poet and novelist have always approached publishing houses and for the most part magazines as if they were neutral at base. And to a great extent they were. The pundit, now as always, faces harsh criticism, personal attacks and reputation sabotage – but most of the time his writing still makes it to an audience. The case is much different for poets and novelists who lack the reliability of partisan publications to launch them. They have now to contend with the absurd situation of nominally neutral magazines and publishing houses, which mask ideological commitments so extreme they would make Savonarola blush.

Comstock’s Corpse

When Edward de Grazia wrote Girls Lean Back Everywhere, his irreplaceable book on literary censorship throughout the 20th century, his chief concern was to find out “how the persons who were most immediately affected by literary censorship – authors and publishers – responded to and felt about it…”[5]

Just thirty years later, we are forced to approach what seems to be the same basic problem from almost diametrically opposed angles. In the first place this is because publishers, no longer the straightforward champions of their writers, are now often one of the most important sources of literary censorship – via “sensitivity readers” and ideological criteria. But in the second place because much of today’s censorship is preemptive – coming largely before publication and functioning as a preventive mechanism. Instead of gatekeepers interested primarily in the quality of a work or a writer’s abilities, we now see gatekeepers interested primarily in the ideological purity of a work and the writer’s identity.

The corollary to this is that the impetus to censorship, as well as reward and punishment criteria, come now primarily from the political left – though in some cases religious conservatives still give them a run for their money. However that might be, it is important to note the incredible similarities and ideological overlap between the Christian censors of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and the “woke” censors and would-be censors of today.

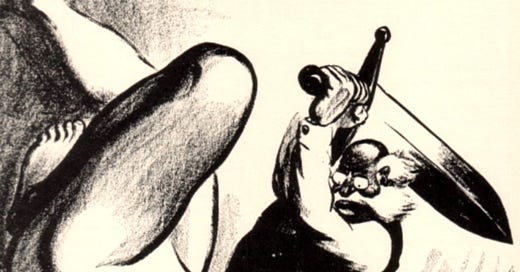

The most illustrative example, both of the old method of literary censorship and of the old reasons for it, are to be seen in the case of Anthony Comstock and the so-called “Comstock laws” that he lobbied for and inspired. Made a “special agent” of the post office in 1873, after years of privately targeting anything he considered immoral, Comstock was empowered to inspect mail and seize any “obscene material,” which included beside literary and erotic written works, informational writings about contraception and abortion, as well as actual contraception, photographs and erotic playing cards.

He and his true believers would routinely seize shipments of books and other printed material they thought obscene or immoral. Indeed, he referred to himself as a “weeder in God’s garden.” Among the classic works of literature the Comstock laws relegated to “weed” status can be listed Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, Bocaccio’s Decameron, Joyce’s Ulysses, Ovid’s Metamorphoses, and Rabelais’ Gargantua and Pantagruel. He was, according to historian Paul Boyer, “devoid of humor, lustful after publicity, and vastly ignorant.”[6] This ignorance extended to raids of fine art galleries, in which, for example, he and his troopers seized photographs and prints of the masterpieces of European painting.

For the next three decades, Comstock would raid galleries, museums, booksellers and publishers, arresting not only authors and artists, but often low-level employees who happened to be working wherever an “offensive” book or picture was displayed or sold. New York newspapers, while occasionally critical of particular blunders, were in general supportive of his work. Support behind the scenes was even stronger: J.P. Morgan, William Dodge, Samuel Colgate and John D. Rockefeller Jr., among other luminaries of the age, contributed enormous sums both to Comstock personally and to his Society for the Suppression of Vice (SSV).[7]

The first thing to notice here is that the desire to censor literary and artistic works was inseparable from the desire to censor not only erotic and pornographic works, but even information about contraception – which Comstock called “articles for immoral purposes”. In other words, an unhealthy obsession with sex, particularly how other people view and relate to sex, seems to have gone hand in hand with a highly moralistic approach to literature, such that only literary works deemed morally acceptable ought to be published. We should also notice that, for Comstock and his crusaders, “morality” was not a problem but a given category, not a debatable and blurry construct but a religious certainty. Those who produced or consumed “immoral” works were not people with a different understanding of what was appropriate, not adults who saw the problem of human action differently, but immoral, fundamentally evil, enemies to be destroyed. And indeed, Comstock bragged that he had driven 15 people to suicide in the course of his career (mostly to avoid financial ruin and imprisonment).

The general institutional support Comstock received during his lifetime cannot be emphasized enough. After Comstock’s death in 1915, even the New York Times summarized his achievements by saying that while he might have gone too far in a handful of instances, on the “merits” of his work, “there never has been or could be any question by decent people…”[8] His achievement, then, was nothing less than “the protecting of society from a detestable and dangerous group of enemies.” Indeed, in his first year as a “special agent” alone, he protected “decent people” from 134,000 pounds of books. And over the course of his life, he bragged that he had immolated on their behalf, “sixteen tons of vampire literature,” along, of course, with condoms, titillating novelty cards, information on birth control and erotic photos and plates.

Preemptive Censorship: Sensitivity Readers

Of course, today’s “woke” censorship isn’t interested in protecting “decent” people from titillating novelty cards – there has been an inversion of terms, such that “decency” has become indecent and sex has begun to be moralized about in exactly the opposite direction as Comstock and his prying soldiers. Today’s enlightened busybodies have made it their mission to protect right-thinking people from any thought, idea or argument that might conceivably conflict with their particular, narrow dogmas regarding sexuality and “gender.” Thus we now see members of the ACLU pushing for the censorship of books that conflict with approved messages on transgenderism.[9]

Similarly, we find so-called “sensitivity readers” employed by major publishing houses (and directly by ideologically possessed authors) to determine whether a work of literature falls within the accepted bounds of woke propriety. These readers function as editors, seeking out instances of racial minorities represented in ways deemed unenlightened (even if they are portrayed positively), portrayals of “gender” that could be construed as “problematic,” and characterizations of non-heterosexuals that for whatever reason raise red flags. They then patiently explain to the writers why their fictional constructs are unacceptable, inferring from their own “lived experience” as “marginalized” people that all others with the same “identities” will have similarly unhappy reactions. Were they paid more, one would almost be jealous of the grift – though, as it is, the rewards, while partly pecuniary, seem to be chiefly ideological: they are rewarded by continuing to be of service to their cause. Much like a missionary who is allowed to found another mission, the goal of the revolutionary is more revolution.

One result of this approach is to codify ideological assumptions about different human types and thereby prevent artistic exploration of human motivations and actions that actually ring true. The process incentivizes the production of simplistic moral tales. Consider: if a transgender character is to be tolerated, according to current orthodoxy, they have to be portrayed positively – which is to say, they cannot be villains or even have ambiguous or conflicted motivations – they cannot, in other words, be real characters at all, but must be avatars of ideal types. The same goes for gays or women or racial minorities. Nuance is thereby essentially forbidden, and every story must affirm prevailing pieties. The mirror is no longer held up to nature, but to prefabricated ideological simulacra.

Here, again, is Alex Perez:

“If you’re a POC, you can’t just submit any old story about the POC experience, but one in which the narrative framing is about victimization at the hands of America and “whiteness” and all the other predictable tropes that now dominate literary fiction. When you write into this framing, you’re performing like a token good boy, hence, you’ve written a token good boy story. The trick to a token good boy story is situating the “brown” characters as victims while also providing the woke white editors palatably edgy scenes that never tip over into the problematic, so they feel like they’re reading an “authentic” POC story. You slip in a word in Spanish or have a character cross the border and dodge a border patrol agent or two; you know, the stuff that makes woke whites salivate. Which is to say that in the literary scene POC characters are only allowed to be victims or noble savages, ideally both—a pure brown person victimized by an evil white system.”

What all of this reminds us of, of course, is the old Christian concept of “morally uplifting” works of art and fiction, as well as Soviet “socialist realism.” In both of these cases, morality is seen as a given framework, not as a problem. It is not something that must be attended to closely, considered carefully, and reassessed in different contexts, but instead something simple, given once and for all, and taken on faith or as a priori judgments. In such cases, the given morality is used as a basic axiom from which all possible considerations can be understood. Socialist man is a higher type, and these are his values – they go against “bourgeois” or individualist ideals and questions. To be a good new man of the socialist type, you must only consult a short list of simplistic virtues and follow them. On the same list you can quickly see which vices are to be jettisoned, fought, reported to the appropriate authorities.

So too with religious “art” – especially at the end of a given tradition. Here too you have simplified, indeed reductive categories and once and for all assessments and guides. Here is your list of sins to be avoided, and here your list of virtues to practice. Characters that embody these virtues are good and can be written. Characters who do not must be cast in the role of villain – if they are to be engaged at all. And in this case they must be portrayed simply and one-dimensionally.

Slate magazine published a piece a few years ago meant to allay growing fears that publishing houses were digging deeper into a self-censorship regime. Yet however hard they tried to spin the facts, their piece is striking in its obliviousness – because a slight change in emphasis would make the article transparently condemnatory of the very thing it tries so desperately to celebrate.

“Freelance sensitivity reader Elizabeth Roderick, who concentrates on bipolar disorder, PTSD, and psychosis—“I’m here to show the world that I’m not, in fact, wearing a tinfoil hat,” she joked—takes aim at language that paints mentally ill characters “as violent, completely unbalanced, and with evil motives.”[11]

That might sound vaguely noble on first blush, but a moment of consideration will raise certain obvious questions: are mentally ill characters never violent or even more to the point unbalanced? Isn’t that actually almost a definition of mental illness – that they are unbalanced? Perhaps the emphasis is the issue. Maybe mentally ill characters can be portrayed as unbalanced – but not completely. If this is the case, it might be interesting to hear how anyone plans to drawn such a line.

A few paragraphs later we hit the question begging jackpot:

“It’s not hard to imagine why sensitivity readers could potentially put authors in a difficult position. After all, where would we be if these experts had subjected our occasionally outrageous and irredeemable canon—Moby Dick or Lolita or any other classic, old, anachronistic book—to their scrutiny? Plenty of fiction—Portnoy’s Complaint, or Martin Amis’ Money—is defined in part by a narrator’s fevered misogyny. Novels like Huckleberry Finn derive some of their intrigue and complexity from the imperfections of their social vision. In Portnoy, for instance, Philip Roth wanted the objectifying gaze of his protagonist—which by default becomes our gaze, since we apprehend the world through him—to make us uncomfortable. Perhaps he even wanted us to use the dubious precepts expressed in the novel to clarify our own beliefs.”

I dislike overuse of the world “Orwellian,” but I’m not sure what else to call this jumble of confusion, question begging and idiocy passing itself off as analysis of the problem. First of all – how did these self-appointed censors, themselves not writers, and typically without the slightest achievements to boast of, suddenly become “experts?” Their expertise, apparently, is the mere fact of their non-cis or non-white identity. From that inanity we move on to another: our canon, we are told, is “outrageous and irredeemable.” Now, this is obviously the considered opinion of our friends at Slate (a tremendously unserious magazine if ever there was one) – but let’s consider for a minute what such a viewpoint implies, especially when taken with its accompanying positive portrayal of “sensitivity readers.”

In the first place, this view implies that self-appointed petty censors with no publications of their own, and without any demonstrated ability to create believable characters, somehow are better positioned to decide what a believable character is and what makes a literary work worth reading than not only the writers who have been suckered into consulting them, but indeed some of the greatest writers in our modern canon – Philip Roth, Vladimir Nabokov, and – to really demonstrate the extent of her vulgar stupidity – Herman Melville.

Perhaps the issue still isn’t clear. Our canon is “outrageous and irredeemable,” containing confused and retrograde minds like Herman Melville – but don’t worry, because an army of petty bureaucrats is going to prevent anything like Moby Dick from seeing the light of day ever again. These nameless moles are going to burrow through all the literature that has a chance of publication and remove everything that might offend minds as small as their own. We are safe, now, thanks to our blinking[12] guardians.

This is the essence of presentism – the assumption that current attitudes and beliefs are unquestionable and righteous, and that all previous beliefs are not only wrong and immoral but no longer acceptable at all, indeed so unacceptable that they sully even the great literary and artistic works which contain them.

And what really amazes is that all of these absurd claims are announced in perfect seriousness, the speaker utterly oblivious to how stupid and petty she sounds. Much like Victorian moralists, proponents of sensitivity readers haven’t even considered that they might be misguided – they have all the earnestness and all of the arrogance of their Christian predecessors. Missionaries at heart, they are very much like Anthony Comstock, who has been called “the apotheosis, the fine flower of Puritanism.”[13] Both feel perfectly comfortable not only rejecting but to varying degrees even condemning well known great works of literature. Comstock’s estimation of Rabelais, Ovid and Chaucer are merely updated in our woke friends’ condemnation of Philip Roth, Herman Melville, and Vladimir Nabokov.

Comstock explained this view explicitly:

“If the newspapers are to be believed, we have been guilty of great indiscretion… and have seriously endangered art and literature. The fact is, we have never interfered with either of these interests, except when we have found them endangering the morals of the young. Morals stand first. Art and literature must adjust themselves to these higher interests.”[14]

Sensitivity readers too have decided that morals stand first. And they have been empowered to prevent immoral – or insufficiently woke – books from ever appearing in print. It should not surprise anyone that 100 years later, we are still starting from moralism and only later on working our way toward literary merit.[15] Comstock too went in for presentist assumptions, arguing that classics should be judged, not by any claims to enduring aesthetic value, but by his chosen moral criteria. He referred to his opponents as “foes to moral purity,” but this was just another way of saying foes to the current assumptions about morality. They happened to be late Victorian assumptions, but that is simply happenstance. Woke moralists are in fact just an upside-down rehash of Comstock and his Anti-Vice crusaders.

Moles and Darkness

Eventually, Comstock began to lose support, and the movement he launched and led seemed increasingly ridiculous. By the second half of the 20th century the culture had shifted enough to allow a series of Supreme Court decisions to end most aspects of the Comstock Laws and to greatly expand 1st amendment protections for free speech. We hope that the same fate is awaiting today’s woke censorship pandemic. But our fear is that it was precisely Comstock’s visibility – the spectacle of his buffoonery – that drove public rejection of his “morals first” approach.

A regime of preemptive censorship, however, is far more insidious because it remains hidden. Comstock was hated by serious people immediately and by large segments of the public later on because what he did could be seen. Books already published were seized; authors of genius and their brave publishers were put on trial. There was a spectacle reasonable people could point to – and spectacles of that kind are, at least in the long run, difficult to ignore. But silent and hidden censorship that takes place before publication? Censorship that snuffs out even the possibility of an author fighting for their work? The only thing for it is to refuse to allow these moles the cover of darkness. If the small-minded censor has learned that silence is a better strategy, his opponents ought to learn as well – learn that we are required to make all of this noxious stupidity visible, so that reasonable people might again make their disapproval known.

In the next section of The Creampuff of Sentimentality we will explore other strategies of woke censorship and contextualize them by comparing them with Christian and Communist methods from the past.

[1] Joyce Carol Oates calls out the censorship of white, male authors | The Post Millennial | thepostmillennial.com

[2] Literary journal in flames after interview with Spectator writer - The Spectator World

[3] Hobart :: Alex Perez on The Iowa Writers’ Workshop, baseball, growing up Cuban-American in Miami & saying goodbye to the literary community (hobartpulp.com)

[4] Publishing industry is overwhelmingly white and female, US study finds | Publishing | The Guardian

[5] Edward de Grazia, Girls Lean Back Everywhere: The Law of Obscenity and the Assault on Genius, 1st ed. (New York: Random House, 1992), p. xiv

[6] Quoted in Craig L. LaMay, “America’s Censor: Anthony Comstock and Free Speech,” Communications and the Law, vol. 19, no. 3, (September 1997), p. 1-60

[7] LaMay, p. 13, 37

[8] De Grazia, p. 6. Indeed, this was laudatory obit was not an exception. According to LaMay, “in his day Comstock embodied the commonly held public view and legal principle that maintaining public decency was within a community's police powers.'” LaMay, p. 5

[9] ACLU lawyer calls for censorship of books that criticize the promotion of transgenderism in children | The Post Millennial | thepostmillennial.com

[10] Martin Scorsese says Marvel movies are 'not cinema' | Martin Scorsese | The Guardian

[11] How “sensitivity readers” from minority groups are changing the book publishing ecosystem. (slate.com)

[12] “We have invented happiness, say the last men, and they blink.”

[13] The Howard Center: The Family In America (archive.ph)

[14] LaMay, p. 28-29, emphasis mine

[15] As we will see clearly when we explore Mencken’s theories of Puritanism in American Art and Literature.

This should be required reading for the new iteration of "the resistance".